The Evolution of Workplace Wellness

Office design has never been static. Over time it has evolved from utilitarian, factory-style workhouses to innovative environments that work to prioritize the mental, physical, and social wellbeing of workers. A growing understanding of how space influences health has led architects, designers, and businesses to rethink how work environments are structured, resulting in workplaces that do more than support productivity—they also support the people who occupy them.

Early Office Environments: From Efficiency to Control

The modern office traces its roots to the 18th and 19th centuries, when administrative functions for governments and industrial enterprises required centralised work spaces. These early offices—like the East India House in London—were designed primarily for surveillance and efficiency. Workers sat in rows, under the watchful eye of supervisors, with no attention given to comfort or wellbeing.

By the early 20th century, the Taylorist approach to workplace design, influenced by Frederick Winslow Taylor’s principles of "scientific management," prioritised maximum efficiency.

Type Pool, early 1900s

These layouts resembled factories: regimented rows of desks, rigid routines, and little daylight or privacy.

Human-Centred Modernism: Frank Lloyd Wright and the Johnson Wax Building

A dramatic shift in workplace design came with rise of modernist architecture, where human-centred architects sought to harmonize form, function, and human needs. One of the most iconic examples is Frank Lloyd Wright’s Johnson Wax Headquarters in Racine, Wisconsin, completed in 1939.

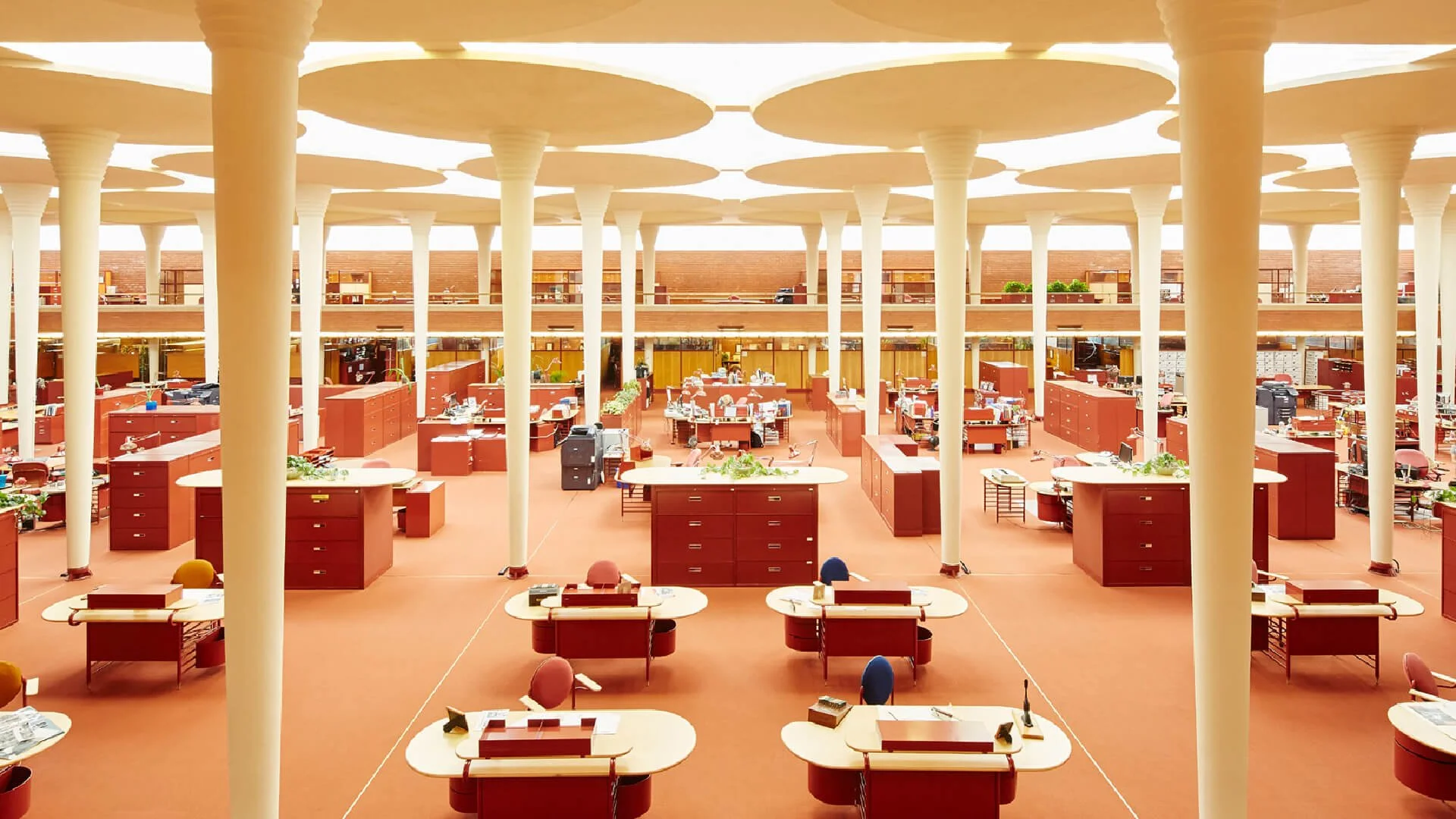

Johnson Wax Building by Frank Lloyd Wright

Wright’s design rejected the crowded, dark office typical of its time. The "Great Workroom" is a vast, open-plan space supported by tree-like (dendriform) columns with skylights that allow the workspace to maximise natural light. The absence of interior walls was intended to foster collaboration and warm materials to create a sense of calm.

Wright described the building as an “open, expressionistic landscape for work,” a stark contrast to the oppressive environments that came before. The design emphasised daylight, airflow, acoustic comfort, and aesthetic experience, marking a clear step toward what we now call "biophilic design"—design that connects humans to nature for wellbeing.

Post-War Design: Cubicles and Control

The optimism of the early modernists gave way to more utilitarian structures in the post-WWII boom. The rise of the Action Office in the 1960s, developed by Robert Propst for Herman Miller, introduced the office cubicle. While originally intended to offer flexibility and privacy, it eventually evolved into cubicles as symbols of isolation and monotony, due to cost-cutting that led to poor implementation of the original design intention.

Action Office, 1960s

Wellbeing took a back seat to density, and the mental health consequences began to manifest in studies linking uninspiring workplaces to stress, burnout, and even physical illness.

Action Office, 1975

The 21st Century Shift: Wellness as a Design Priority

The late 20th and early 21st centuries saw renewed interest in human-centred design. Concepts like ergonomics, indoor air quality, natural light, and access to green space became increasingly important.

The Office Group, 2023

Contemporary office design increasingly incorporates:

Activity-based work environments, where employees choose different spaces depending on task.

Biophilic design elements such as living walls, natural materials, and daylight.

Sustainable practices, like non-toxic materials and energy-efficient HVAC systems.

Mental health considerations, including quiet rooms and flexible scheduling.

Organizations now pursue certifications like WELL Building Standard and LEED, which emphasize environmental and human health criteria.

A Return to Wright’s Vision?

In many ways, today’s workplace wellness movement circles back to ideals Frank Lloyd Wright embraced in the Johnson Wax Headquarters: light, openness, connection to nature, and the elevation of the work experience.

Interested in more?

Duffy, F. (1997). The New Office. Conran Octopus.

Herman Miller. The Office as Facility Based on Change.

International WELL Building Institute. (2020). WELL Building Standard v2.

Saval, N. (2014). Cubed: A Secret History of the Workplace. Doubleday.

Twombly, R. C. (1979). Frank Lloyd Wright: His Life and Architecture. Wiley.